‘How did we get here?’: documentary explores how Republicans changed course on the climate

In The White House Effect, now available on Netflix, archival footage is used to show how the US right moved from believing to disputing the climate crisis

Adrian HortonTue 4 Nov 2025 10.02 GMT

Share

In 1988, the United States entered into its worst drought since the Dust Bowl. Crops withered in fields nationwide, part of an estimated $60bn in damage ($160bn in 2025). Dust storms swept the midwest and northern Great Plains. Cities instituted water restrictions. That summer, unrelentingly hot temperatures killed between 5,000 and 10,000 people, and Yellowstone national park suffered the worst wildfire in its history.

‘How is this possible?’: a new film looks inside the appalling abuses of the Alabama prison system

Read more

Amid the disaster, George HW Bush, then Ronald Reagan’s vice-president, met with farmers in Michigan reeling from crop losses. Bush, the Republican candidate for president, consoled them: if elected, he would be the environmental president. He acknowledged the reality of intensifying heatwaves – the “greenhouse effect”, to use the scientific parlance of the day – with blunt clarity: the burning of fossil fuels contributed excess carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, leading to global warming. But though the scale of the problem could seem “impossible”, he assured the farmers that “those who think we’re powerless to do anything about this greenhouse effect are forgetting about the White House Effect” – the impact of sound environmental policy for the leading consumer of fossil fuels. Curbing emissions, he said, was “the common agenda of the future.”

That clip – startling to anyone even glancingly familiar with Republican orthodoxy in the years since – appears early in The White House Effect, a new all-archival documentary that examines the evolution of the climate crisis from non-partisan reality to divisive political issue. The 96-minute film, now available on Netflix, takes its name from Bush’s unfulfilled guarantee of environmental action during his four years as president, a pivotal missed opportunity – if not, as the film implicitly argues, the pivotal missed opportunity – for bipartisan US leadership on the climate crisis. “There was this moment in time when the science was widely accepted, when the public was all about tackling this,” co-director Pedro Kos told the Guardian. “It was a mom and pop issue, as American as apple pie. Flash forward to four years later, and you have a completely split electorate. How do we get there?”

The film, directed by Kos with Jon Shenk and Bonni Cohen, first rewinds the clock from Bush’s uncontroversial campaign promise back to the 1970s, when the science on the greenhouse effect became a public talking point. In news footage from the late 70s, ordinary Americans react to then President Jimmy Carter’s exhortation to face “a problem that’s unprecedented in our history” with patriotic enthusiasm; sacrifices, they confirm, may be necessary. By the early 1980s, faced with a gas shortages and hours-long lines at the pump, some of that enthusiasm had crumbled. As the Republican presidential candidate, Reagan responded to the discontent by blaming the government and calling for authority to be transferred back to the private sector (or, to use a Reagan euphemism, “experts in the field”) – setting the stage for the Republican party’s symbiotic relationship with large oil companies well aware of the impact of emissions on the climate. (To quote an internal Exxon document from 1984: “We can either adapt our civilization to a warmer planet or avoid the problem by sharply curtailing the use of fossil fuels.”)

But the film largely focuses on Bush, a blue blood east coaster who made his fortune in the Texas oilfields, and who nevertheless began his term in office in 1989 determined, at least outwardly, to break from his predecessor on the environment. Bush appointed an environmental activist, William Reilly, as head of the Environmental Protection Agency; he exhorted Congress that “the time for action is now.” The White House Effect illustrates the political forces that eroded such purpose: the corporations that, according to their own internal documents, sought to downplay and discredit scientific evidence to protect their profit; the power games by White House chief of staff John Sununu, an ally of corporate lobbyists who outmaneuvered Reilly by encouraging climate skepticism in the aftermath of disasters such as Hurricane Hugo and the devastating Exxon-Valdez oil spill.

The film works exclusively with meticulously edited archival footage – the team sorted through more than 14,000 clips from more than 100 sources, including VHS tapes stored in the New Jersey garage of a former Exxon Mobil publicist and a memo from a confidential “Global Warming Scientific ‘Skeptics’ Meeting” convened in 1991 by Sununu to empower media appearances by prominent climate contrarians. The reliance on archival was part of an effort to “immerse the public in a time when this wasn’t a political football – where we experience the politicization of the issue, rather than being told it,” said Kos. “Whenever you turn on a camera and interview someone in the present, that’s automatically going to come with the political connotations that the present brings.”

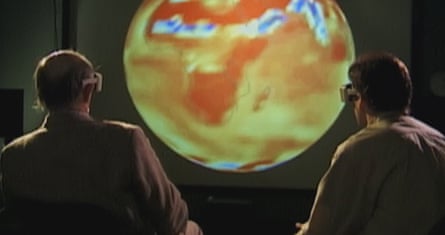

View image in fullscreenA still from The White House Effect. Photograph: Netflix

View image in fullscreenA still from The White House Effect. Photograph: NetflixCohen and Shenk are veterans of climate change films; the married couple directed An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power, the follow-up to Al Gore’s groundbreaking documentary on looming climate catastrophe. But with The White House Effect, “we wanted to do something very different from what we’ve done in our past work and what we think of as the ‘climate change genre’ of documentaries: we wanted to just drop the truth bomb of history,” said Shenk. “We need that, right? We just need the truth.”

With archival, there’s “an opportunity to expand the conversation,” Cohen added. From man-on-the-street interviews to standard network broadcasts from the period, “hopefully you can see yourself in the film no matter who you are as an American, and feel that you’re part of the conversation, rather than some liberal film-makers preaching at you.”

The platforming of climate skeptics on mainstream media and Sununu’s counsel seemed to have an effect on Bush. By 1990, speaking at a White House conference on the climate crisis, he equivocated where he once held firm: “One scientist argued that if we keep burning fossil fuels at today’s rate, by the end of the next century, Earth could be 9F warmer than today. And the other scientist saw no evidence of rapid change,” he said. “Two scientists, two diametrically opposed points of view. Now, where does that leave us?” It left the US hamstrung by political division. Two years later, the “environmental president” reluctantly attended the 1992 Rio “Earth Summit”, a major United Nations conference to set international targets for emissions reductions, advocating against such measures in the name of economic development and stability. The move, from the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, angered other countries, but Bush chided the international coalition: “I don’t think leadership is going along with the mob.” The seeds for outright climate denial, and the Republican party’s unfettered and open alliance with corporate interests, had been sown.

View image in fullscreenA still from The White House Effect. Photograph: Netflix

View image in fullscreenA still from The White House Effect. Photograph: NetflixNearly three decades later, in 2019, Reilly rued how the US missed an “incalculably important” opportunity at Rio. “The advantage we might have had if president Bush had committed to seriously undertake the reduction of greenhouse gases is that we might have removed the partisan nature of the dialogue in the United States,” he said. If that prospect, in the era of hyper-partisanship, increasingly absurd natural disasters and the Trump administration’s dismantling of environmental regulation, feels deeply infuriating – well, Cohen argued, that’s the point. “Climate change films, at least in the last 10 years, have been trying to spoon-feed the medicine of the climate crisis, and then have a ‘hope bucket’ at the end, where you can feel OK,” she said. “Our job is to create the rage. We can’t shy away from the rage. And if this film, in all of its irrefutable archival historical glory, can create that rage, then we’ve succeeded.”

The hope, she added, is that “you can feel the rage and you can feel the intolerance for the denial of truth, and that you’ll actually do something about at the ballot box. The hopelessness is when you feel like you can’t do anything. But we have a large electorate in this country – let’s get out there.”

Kos, having overseen the mass archival effort, encouraged viewers to look at “the overall arc of history” – even in the face of the Los Angeles fires, the Texas floods, the rapid and unprecedented intensification of hurricanes like the one that devastated Jamaica just last week – “what good is despair going to do?” The truth of political power, for good and for ill, is “right there in front of our eyes.”

“The choice is in our hands,” he added. “We’ve shown you a what-if moment from 1988. We’re now in another what-if moment.”

The White House Effect is now available on Netflix

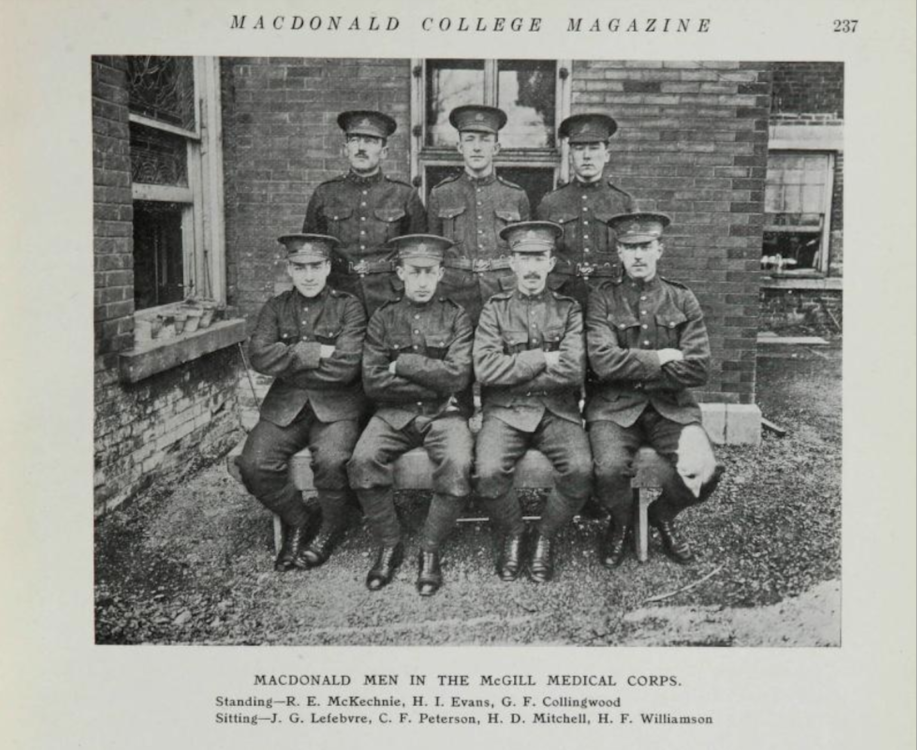

Members of Macdonald College who had enlisted in the McGill Medical Corps. From the February-March 1915 issue of Macdonald Campus Magazine

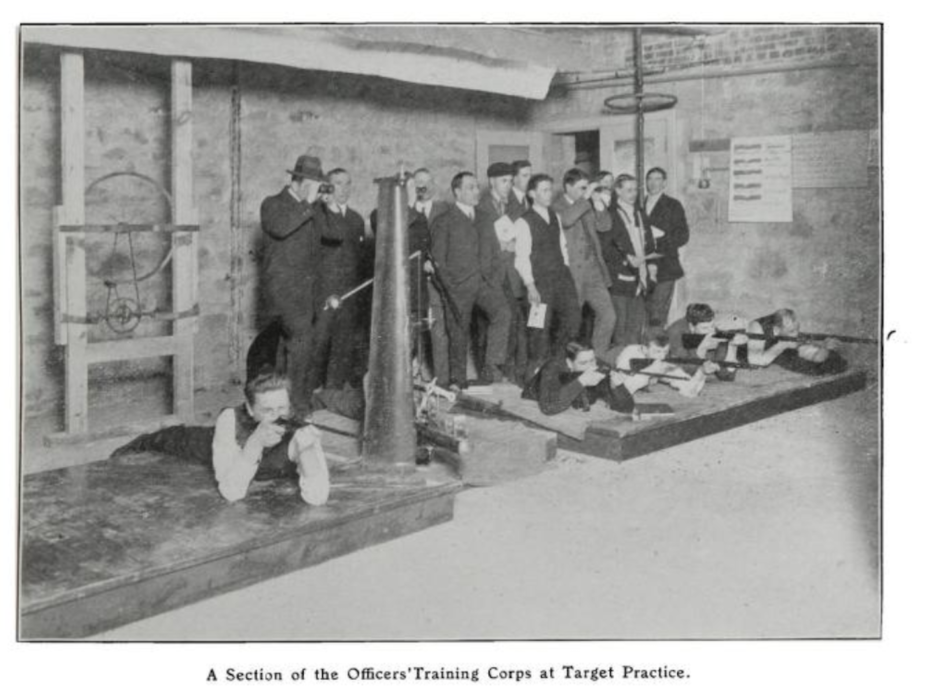

Members of Macdonald College who had enlisted in the McGill Medical Corps. From the February-March 1915 issue of Macdonald Campus Magazine Members of Macdonald College take target practice as part of the on-campus Officers’ Training Corps

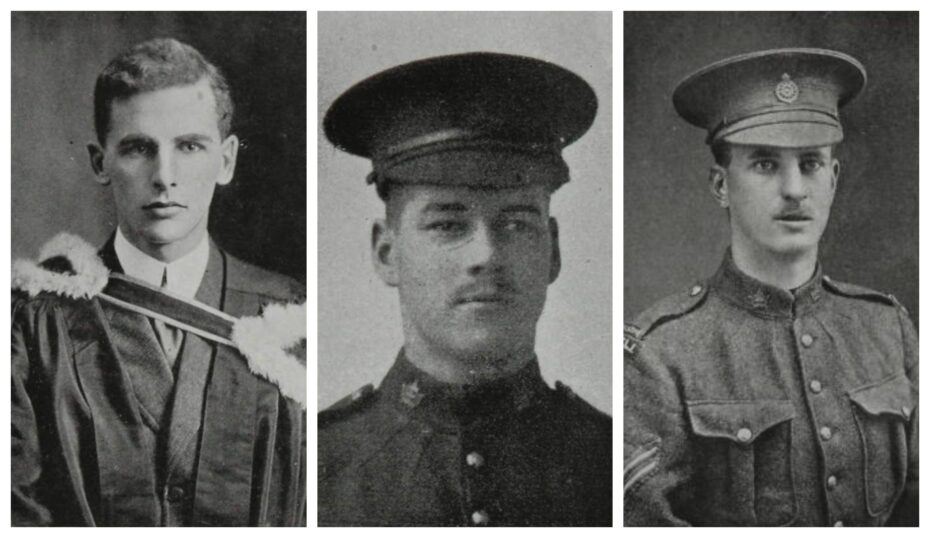

Members of Macdonald College take target practice as part of the on-campus Officers’ Training Corps From left to right: W.D. Ford, Julius G. Richardson and James H. McCormick were the first three members of Macdonald College to be killed in action during the First World War

From left to right: W.D. Ford, Julius G. Richardson and James H. McCormick were the first three members of Macdonald College to be killed in action during the First World War